The Atticus of My Life

In the book of love’s own dreams

Where all the print is blood

Where all the pages are my days

And all my lights grow old

— Attics of My Life, by Robert Hunter

THIS POST IS FULL OF SPOILERS:

If you hate spoilers and plan to read Go Set a Watchman, skip this post for now.

But please, come back when you’re done.

A piece of free advice:

If you have not read To Kill a Mockingbird recently, read it before you read

Go Set a Watchman. You’ll be glad you did.

I’m one of those peculiar people who take literature too seriously. I’ve never doubted the power of a good writer to create worlds that are as real as our own and, at the same time, to conjure reflections and echoes of a reality we haven’t quite earned yet.

Characters in books become as real to me as my friends and family, my banes and enemies. I grant that this is a sign of deficient mental health, but I hope I’m not the only one who, for example, bursts into tears when Gavroche Thénardier dies on the barricade or when Edgar Derby is executed for pocketing that damned teapot he found in the rubble. I guess most times for most people, characters remain on the page where they belong and don’t much interfere in our day to day. Lucky them?

But some characters escape the page and grow larger than life, become icons. Some, like Atticus Finch, become moral exemplars and redeemers of collective wrongdoing. And if there’s anything we can’t stand, it’s for someone to reveal the flawed man behind the myth.<fn>See also, Huxtable, Cliff.</fn>

So let’s cut to the chase. Atticus Finch is a standard issue Southern gentleman – a man I recognize well in several of my Deep South forbears – a genteel fellow of manners and decency who also happens to hold racist views that are extreme enough to make the daughter who once idolized her Perfect Father literally throw up when she discovers his true nature.

It’s easy to see why so many long-time Harper Lee fans are outraged.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Lee created the Great White Father, the man of infinite patience, rectitude, and sense of fairness who could redeem our (White folks, that is) sense of guilt and discomfort over racial injustice. In Go Set a Watchman, she pulls the curtain back to reveal that Atticus, the Great and Powerful, is just another worn out, cranky uncle forwarding conspiracy emails and ranting about Those People. Once again, hero worship turns out to be a sucker play.

At the end of Mockingbird, we were given permission to tut-tut the horror of Tom Robinson’s predicament and to feel joy at the progress we’ve made, pass the chicken please. The white trash Ewells excelled in the Judas role in this passion play, lowly creatures who took welfare and kept their kids out of school and couldn’t be bothered to shift for themselves. Our own hands were never dirtied like the coarse and common Ewells. They were the evil in our midst, and if only we better whites could follow the shining example of Atticus Finch, the world would be our Nirvana, and hallelujah, pass the gravy, if it’s not too much trouble.

Watchman‘s Chapter 17 is one of the most painful reading experiences I’ve ever suffered. Even knowing ahead of time that Lee was going to reveal a “dark side” of Atticus, I was unprepared for the casual, genteel, typically Southern bigotry coming out of his mouth. And Lee wrote this exchange with no wiggle room: Atticus is basically a disgusting racist. He laughs at Jean Louise’s arguments, he taunts her for her naivete.

There’s no turning away: the Great White Father is a son of a bitch. The revelation of Atticus’s repellent attitudes hits as hard as if a sequel to the gospels revealed that Jesus and Judas were the same character. Everything you know is wrong.

A few days before GSAW hit the stores, I re-read Mockingbird for the first time in years. I was surprised at the extent to which the movie depiction replaced the book itself in my memory.<fn>Like I said: re-read TKAM before you read GSAW.</fn> Mockingbird the movie revolves around the trial of Tom Robinson; everything else that happens travels in orbit around that event. In the book, the trial is critical, but the book as a whole explores the curve of small-town childhood in the South with fondness and wit. (White children, naturally.) As with so many movies/books/tv shows about race, actual black folks are pretty much in the margins.<fn>With the notable and long overdue exception of the movie Selma, though it too has its own issues of Great Father drama and hagiography.</fn> And this gets to one of the key problems with Mockingbird – on the one hand, it asks us to empathize with the ‘poor, poor Negro’, even while bestowing upon us a glimmering savior to make us all feel okay again. That nice (hell, impossibly perfect) Atticus washes our sins away.

While theories abound as to Watchman’s origin, I readily accept that this was an early shot at Lee’s Maycomb chronicle; after reading Watchman, Lee’s editor told her go back and tell the tale from Young Scout’s perspective. It took her two years to re-write, and the result was the structurally and stylistically superior Mockingbird. The Watchman version is clearly unfinished; it lacks the cohesion that extended editing and re-writing would have instilled.<fn>It is also unmistakably the work of Harper Lee. This is no hoax, and it sure as hell is not Capote.</fn> But I can also see how this might have become, later on, an effective sequel. In fact, it takes great effort to read this as anything other than a sequel or amplification of the original: the same characters, 15 years later on the fictional timeline, in a book published 50+ years later. It’s of a piece, and it provides an essential corrective element that turns the saga into something other than a happy fairy tale, albeit one where that poor Tom Robinson &c., pass the black eyed peas.

Mockingbird gave us a feel-good fantasy. Watchman fills in the blanks and gives us a truth that does not encourage happy mealtime discussion.

Mockingbird is still a great novel. Lee’s depictions of the rhythms and rhymes and smells of Southern life are as good as anybody else, Faulkner, O’Connor, Percy, you name your favorite. But Harper Lee is not a great novelist.<fn> For the same reason the John Kennedy Toole and Joseph Heller are not; the body of work is just not there to justify such a judgement.</fn> She spread a dusting of fiction over the people she knew growing up, the place she knew. She had a story worth telling, and perhaps even recognized that the time had come for white southerners to address race in a different way. But she had one good story, told it, and went silent. Wondering whether she could have become a great novelist is no better than a parlor game along the lines of could Wilt Chamberlain outplay Michael Jordan and such.

While Watchman is not a great novel by any stretch, it’s probably not fair to judge it too harshly given that it never even made it to galleys until its rediscovery. But it is an important piece of work for two key reasons. First off, it sheds light on the author’s struggle, the process of taking a work from idea to paper to woodshed to completion. This alone would make GSAW a worthy curiosity for literary scholars and a fun what-if exercise for Mockingbird devotees. But more important than this: Watchman uses the Freudian/Oedipal device of kill the father to allow Jean Louise to become an adult in her own right. And in so doing, Lee strips the mask from a false idol that has captivated her fans for several generations. And that shit comes with some heavy dues.

So first: The similarities between TKAM and GSAW are evident and plenty, with several paragraphs that describe Maycomb life appearing in both without so much as a comma’s difference. But the divergences are where we get a glimpse at the evolution of a book that has been read by millions of people over the past half century.

Famously, Tom Robinson is convicted and then killed trying to escape prison; everybody knows that. But in Watchman, the “trial” is dealt with in a paragraph or two, with the throwaway reference that Tom was acquitted.<fn>And a more disturbing suggestion that Atticus fought hard for Tom only to sustain the fiction of equality under the law. More later.</fn> In the retelling, the “trial” transformed from a mere trifle to the centerpiece of one of the nation’s great moral fables.

Then there’s the fiance in GSAW, Henry, who Jean Louise describes as her oldest and dearest friend, a boy who lived across the street at the same time the trial and the adventures with Jem and Dill and Boo played out. This character does not exist in Mockingbird. Perhaps even more revealing, Boo Radley does not exist in the Watchman universe, and there is no mention of Bob Ewell’s attack on Jem and Scout, the event that provides the bookend beginning/ending of the entire Mockingbird narrative.

And of course, there is Jean Louise’s discovery and outrage that the Father and her fiance are, if not card carriers, at the very least fellow travellers of the White Citizens Councils who made damned well and sure that Jim Crow remained the law of the land and kept Those People from getting above their station. Not to be outdone, Jean Louise reveals herself to be a states rights fanatic of the first degree, and declared herself angry and outraged that the Supreme Court would force people to do the right thing when they would certainly get around to it in their own good time and why are they rushing things so. Between the two of them, you have the complete package of racial oppression. And they’re both so damned reasonable about it.

The heart of Watchman‘s ultimate importance lies in that last disparity between what might be viewed as the canon of TKAM and the heresy of GSA, lies in Harper Lee’s forcing us to squarely face the myth of the Great Father, to see the truth of the complexity and the ugliness and duplicity, and to, well basically, grow the fuck up. Look, she says – you worshipped this False Idol, you used him to absolve your sins, and you’ve been a dupe the whole time. And by the way, your stand-in Scout ain’t all that either, what with her love of states rights and eventual acceptance of the way things are.<fn>To be sure, the ending of the book feels hurried and undeveloped, something I feel would have been addressed in re-write/editing. But Lee said publish it warts and all, so this is the text we have to unpack, to use a term that I hate but why not at this point, my god, the world is in tatters and the Great Father is dead. Cut me some slack.</fn>

Lee created the Perfect Father, the man who could resolve any argument, cure any scratch or scrape. And Gregory Peck made that character flesh. Go ahead, try to imagine any other actor of the past 100 years in that role. None of them will stick. One stupid internet poll after another has put Atticus near the top of the “perfect father” sweepstakes. People name their children after Atticus. He’s a goddamned monument.

And this is exactly where Watchman delivers the blow that makes it an important contribution to this corner of the literary world: Lee shows us that our Savior is a fraud, tells us to wake up and be adults in our own right. Lee shows us the essential error of putting our faith in mythical heroes and asks us to stand on our own. Sure, it’s tough when we discover that the pleasing fairy tales of our childhoods are fictions that cover up a more complex and disappointing set of truths. Step up and deal.

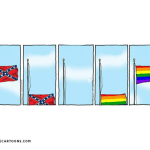

Watchman comes along at a particularly fraught moment in our 400 year struggle with the wages of America’s original sin. Any pretense to having arrived at a post-racial moment withers with the first serious investigation. No matter how “good” we whites think ourselves, no matter how much we congratulate ourselves on how far we’ve come<fn> Guilty as charged. Mea culpa.</fn> – the fact remains that we live in a segregated society, and it is primarily White America’s obligation to ensure that the structural changes necessary to allow this issue to reach resolution are squarely in our own laps. (Like it or not, Blacks have no obligation to make things better; we shit this bed and it’s ours to clean.) Unlike TKAM, Watchman does not offer any bromides to make that pill any less bitter. In fact, by making Atticus’ noble defense of Tom Robinson an act of expedience rather than principle, Lee drives home a disturbing and cynical point: good deeds may not quite be what they appear. Even your own, so stay awake and question, question, question.

Another heartbreaker in Watchman: Jean Louise pays a visit to Calpurnia, the Negro woman who essentially raised her and Jem. In TKAM, Calpurnia was for all intents the only Mother Jem and Scout knew. Now long since retired and removed from the White world, Calpurnia barely acknowledges Jean Louise, and certainly display no affection. Jean Louise is deeply hurt, but also outraged: how dare she not remember me, how dare she turn her back on how good we were to her, how we treated her as though she were just like family, etc. Jean Louise has not found the maturity to accept her own complicity in racial oppression. It’s too much for her to take. In this, she is the perfect representation of too many “enlightened” whites on the question of race, with our plaintive whines of “can’t they see how much we/I have done for them already?”, largely blind to the overwhelming privilege we claim as our birthright without even recognizing it even exists.

In the end, I find myself at this: despite the fact that Mockingbird is likely to remain the preferred version of Lee’s Maycomb tales, it is dishonest to ignore the details of Watchman in our overall view of what Maycomb means in its literary context. Memories are imperfect, and stories told over time shift and morph to reflect new experiences, changed attitudes, or something as simple as wish fulfillment. When Lee wrote Watchman, she told a story of a young woman’s disillusionment about her once revered father; when she rewrote the story from the young Scout perspective, she transformed Atticus into the perfect father, the perfect man.

This is not necessarily a contradiction. But the fuller portrait that emerges from the combined tellings – even though it is a real heartbreaker – brings us closer to an understanding that is probably more useful and true in the long run: we are none of us perfect – even/especially the people you’ve placed on a pedestal – and you can bet there’s a dark side to your own character that needs serious work, some whining cling to privilege that we mostly don’t even see. And there is no Great Father who can fix everything for us; it all depends on our own imperfect efforts. It is surely impossible to bear, to go on without our Great Father; but the alternative – giving up and throwing in the towel – is even worse.

I’m not sure Harper Lee intended anything of the sort. It may be that she truly felt the story delivered in Mockingbird is the “way it is”, and I’ve no doubt many will hold to that reading. But I’ll hold to this one: Harper Lee knew what was in the earlier manuscript, and she allowed its publication as a favor to us all. Watchman delivers a harsh but necessary message: Give up the fantasy and face the world as it is. Shit’s too damned serious for anything else.