Oh for the love of….

Well here we are again, a gaggle of bible thumpers declaring victimhood because a book threatens the very ground of their beliefs.

It’s bad enough when a parent helicopters into a school to protect his little precious from bad words and strange ideas. But now we have college students sheltering themselves from the horror of a broad education. Assigned a graphic novel<fn>In my day, we called them comic books, and we liked it.</fn> for summer reading, freshman enrollee Brian Grasso, Duke University Class of ’19, took a look at Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and declared that he would not read it because of the book’s “graphic visual depictions of sexuality”.

I feel as if I would have to compromise my personal Christian moral beliefs to read it,” Grasso wrote in the post.

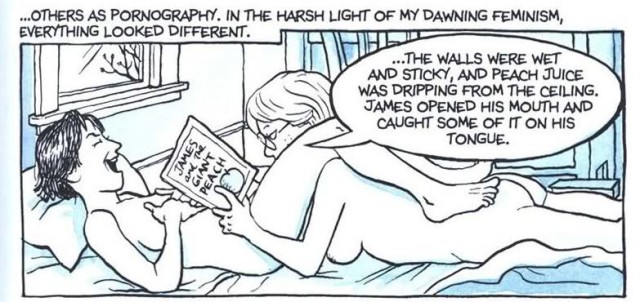

FWIW, the so-called “graphic visual depictions of sexuality” are all icky gay stuff. Naturally. To wit:

Another student wrote in an email that:

The nature of ‘Fun Home’ means that content that I might have consented to read in print now violates my conscience due to its pornographic nature.”

It’s hard to tell, but I think this means he would have been okay with reading a steamy sex scene, but a pen and ink illustration of same would threaten his mortal soul. The grammar and theology behind the email make for a tough nut, crackwise. Perhaps it has to do with the confusion this book might create in re: a beloved children’s book:

I must lead a sheltered life, but I had not heard of this book before today. Now, thanks to the squeamish guardians of morality in Duke’s Class of ’19 – and, to be honest, this intermède de peche juteaux – it has risen to the top of my to-read pile.

There’s a bit of a skewed parallel between this kerfuffle and last week’s tempest over The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime<fn>Is a skewed parallel even a thing? Geomathematically, perhaps not, but I’m kind of loving the challenge of visualizing one, so a thing it is, says I. If this offends, you can either write your own blog or organize a protest against my invocation of such an abomination to Euclidean purity.</fn>. In that case, it was busybody parents invoking their right to “raise their children as they see fit” while not so incidentally depriving the children of less hysterical parentage the opportunity to grapple with new ideas.

In this week’s episode in willful ignorance, it is the busybodies’ spawn invoking the right to remain unsullied by ideas that are new or unusual.

School-wide book assignments for incoming freshmen are a staple of college curricula these days. It provides a nexus for the entire incoming cohort to discuss, debate, and argue the merits/cons of a specific work. It does not ask that anyone abandon their faith or accept a new idea that offends them.

It does, however, ask that students at least consider a perspective that may be new to them. It asks them to begin to think for themselves, to analyze information that is new and challenging. And that, alas, seems to be the core of the offense that these tender lads and lasses cannot bear.

Exposure =/= indoctrination. Is their belief set so tenuous that a comic book would cast it asunder?

“I thought to myself, ‘What kind of school am I going to?’” said freshman Elizabeth Snyder-Mounts.

You’re going to Duke University, child, source of 8 Nobel laureates, 3 Turing Award winners, and 25 Churchill scholars. These are not honors that typically accrue to people who are afraid of a comic book. Duke has no religious affiliation. It has ranked in the top ten US universities for the past 20 years.

Duke did not seem to have people like me in mind,” Grasso said. “It was like Duke didn’t know we existed, which surprises me.”

More likely, Duke knows people like Grasso exist and they don’t care about catering to their narrow minds. Universities exist (at least in theory) to expand the minds of its students, to give them access and exposure to information that falls outside the experiences they bring to campus. If a student does not wish to have his tender feelings bruised from an encounter with new ideas, there is a simple solution: stay home. Get a job or go to a trade school.<fn>Or go to one of the bible-based schools where the mission is to keep you safely cocooned inside your ignorance.</fn>

The student is asked to read a book, not adopt it as a how-to-live manual. The student is asked to bring a sense of skepticism to the exercise, to read with critical awareness, and to come to some conclusions about what they do/do not believe. Until the next book, and then it happens again, believing something new, discarding something old, re-believing something old, and so on. In the end, the student arrives at some semblance of understanding herself – what she believes, what she is willing to fight for, what she holds dear.

“In the end.”

I suppose I should reveal the deep, dark secret around this: there is no “end” to all this. It lasts a lifetime. This may be the most wonderfully maddening aspect of being an alive, alert human being. Exposure to a range of ideas in the course of one’s education is a terrific foundation for this kind of rich, multi-layered life.<fn>Of course, this D.D. secret might be terrifying to some, to those who want an answer now that will confer certainty and foundation to every challenge that will come their way. These are the people who wish to protect themselves from strange new ideas. Those things shake the earth beneath our feet. Scary stuff.

I will give the frightened flowers of Duke’s Class of ’19 this much: They are not trying to impose their fear of learning on anyone else. They just want to be able to close their senses to something that scares them. And the powers at Duke are letting them have their way. That’s probably as it should be. You can lead a horse to water.<fn>Or you can lead a horticulture &c.</fn> But somewhere, somehow, a strange idea is going to sneak through and these students will be utterly unprepared for the shock.

By the same token, students who invoke the recently-minted trigger warning concept should also receive consideration. If someone really, really objects to certain kinds of material – for whatever sincerely held reason – she should be allowed to opt for an alternate curriculum. Perhaps that student should reconsider his field of study if this happens too often, just as those who feel that religion makes them incapable of fulfilling their professional duties should consider a different line of work.<fn>Mennonite airline pilots, perhaps?</fn> But in no case should the sincerely held beliefs of one, or a few, or even of a majority, be used to interfere with the rights of everyone else to learn what the school offers to teach them. And if your school insists on teaching you about knowledge you’d rather not deal with, go somewhere else.<fn>I’m pretty sure I would not appreciate the curriculum at Bob Jones University.</fn> And it’s way past time our society stopped privileging complaints based on religion over other kinds of objections. If a student really wants out, let her out, whether it’s because of religion or gluten or an objection to the teacher’s cologne. And everybody else goes on with their business.

As it happens, as I was writing this lament about how some kids these days are wasting their opportunity to learn and to embrace their humanity in full, I was alerted to a new opinion piece in our local fishwrap in which one of the local students affected by the Curious Dog kerfuffle lamented the loss she felt from the affair. This is a young woman whose curiosity for new ideas is undampened.

Here’s a point J.W. makes well:

Telling students to avoid books containing “wayward beliefs” implies we are incapable of thinking for ourselves. The removal did not give parents the freedom to parent, but instead attacked freedom of thought.”

That’s the story in a nutshell. The fear of ideas and the attempt to run away from them, to pretend they don’t exist, leads to nothing good. Suppressed ideas become alluring, forbidden fruit, suffused with the aura of being “naughty” or “bad”. The refusal to grapple with them in the light gives them greater power. And when the time comes – and you bet your last dollar it will – when the time comes that the sheltered innocents are forced to face the world as it is, the ground will shake and the walls will crumble. This story is as old as time.

I worry about the students who are supposedly ‘getting an education’ when all they are really getting is a piece of paper that says they hung around for 4 years or so. These people are a danger to themselves and to our society’s ability to govern itself.

But then again, students like J.W. and all the others like her – curious, awake, alive – just might give this cynical old coot cause for optimism. <fn>For real.</fn>