Ears Embiggened – 50 Years of Great Black Music: Ancient to the Future

(The second in a series of preview posts as we count down to the

2019 Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, TN. Part 1 here on the 50 year legacy of ECM Records.)

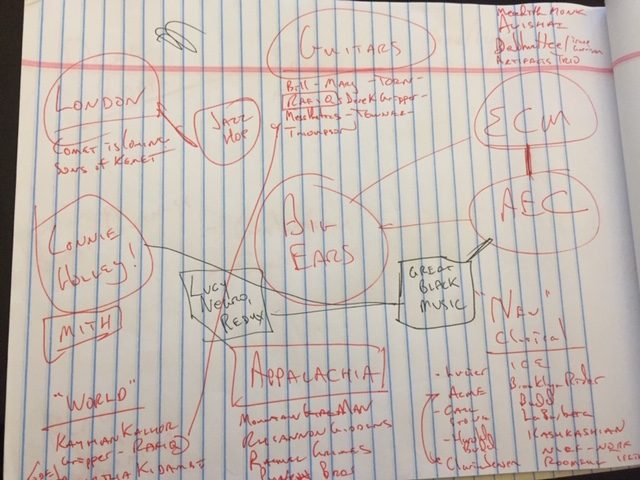

Among the highlights of Big Ears Festival 2019 are the coinciding 50th anniversary celebrations of ECM Records and the Art Ensemble of Chicago. There is a book to be written about Big Ears in general, and this round-number accident of the calendar in particular is fertile ground for way too much rumination for a couple of blog posts, but I will try to put a fence around it.

1969, the ostensible birth year of ECM and AEC, was the height of what pop history shorthands as the ‘counterculture’, that period of social, political, and artistic upheaval that continues to wield influence on both actual culture and nostalgic cable teevee documentaries intoning vapid bromides about upheavals, nothing would ever be the same, and so on. But it is easy to get jaded and glassy-eyed at the pabulum narrative and to forget that, yeah dammit, shit was going down, and even if some of it was not really “new”, there was a critical mass of interest and action that gave some of the ideas and movements a heft that we would be foolish to forget.

One not-new idea held that communal living and collaborative decision-making could serve as a corrective to our degraded society. This led to a flood of collectives and communes and cooperative organizations, most of which came and went, victim to the usual parade of suspects: infighting, drugs, petty jealousies, personality cultism, bad weather, and so on. In large part, the failures were baked in the cake from the outset, as the children of relative privilege known as hippies<fn>I resemble that remark.</fn> were hamstrung by unrealistic expectations and nihilist fantasies. Many a Utopian adventure launched with insufficient appreciation for what it might take to make such a project work. For their trouble, they were in large part allowed to fail and then regain their position in privileged society, filled with contrition for their wayward apostasy while still indulging their fantasy of somehow standing up to “the man” that many of them would someday become. That many of these so-called vanguard became enthusiasatic cheerleaders for the worst in Reagan’s Morning in America should come as no surprise.<fn>Also, too: take a look at the last presidential vote for indication of how this demographic cohort, well-educated and flush with 401k, turned out for Trump. The boomer track record ain’t pretty.</fn>

Not all such groups were born of rainbow and unicorn wishful thinking. In situations where collective action was in fact a predicate for survival, the mission and sense of responsibility was somewhat more clearly defined. Groups with clearer vision of what their community needed, like the Black Panthers, created support systems to deliver essential services to their neighbors. Theirs was an ethos of self-sufficiency and discipline that aimed to uplift a marginalized community. For their trouble, they were targeted for elimination by a paranoid government, some murdered in their beds.

In the middle of this ferment, in 1965, a group of musicians on Chicago’s South Side formed the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. Predominantly African-American, the AACM performed each others’ compositions, worked each other’s concerts, pooled resources, and so on. The AACM also offered music lessons to kids and played benefit concerts for community needs. Several of the most important musicians of the late-20th century (Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Muhal Richard Abrams, and a couple dozen more) emerged from the AACM orbit. The place was as much a community center as it was an incubator for a musical movement.

In 1966, multi-reedist Roscoe Mitchell assembled an AACM sextet that included trumpeter Lester Bowie and bassist Malachi Favors to record Sound for the Delmark Records label. Much of the so-called free jazz at this time was wall of sound onslaught, typified by Coltrane’s late period and the take no prisoners approach of Ayler, Shepp, and so on. Sound was notable for its cultivation of space and silence. Passages would float one into the other like clouds, leaving the listener feeling eerily like a cartoon character who just stepped off a cliff, suspended in time just ahead of a free fall. It was composed and improvised in a way that set it apart from just about anything else on the scene at the time.

The story goes that Mitchell convinced an employee of Delmark, Chuck Nessa, to get this album recorded and released. (Delmark was primarily known as a trad jazz and blues label, and a damned fine one at that.) A year later Numbers 1&2, released on the new Nessa Records label under Lester Bowie’s name and with multi-reedist Joseph Jarman added to the mix, established the core lineup of the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble. The story goes that Mitchell had persuaded Nessa to start his own record label. That label, like ECM, is still releasing vital recordings 50 years later.<fn>At the 2018 Big Ears Fest, when festival promoter AC was introduced to Chuck Nessa, he said, “You are the reason I am here.”</fn>

By 1969, the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble had relocated to the outskirts of Paris, itself the locus of several strains of political and social pushback. As they embarked on a phenomenally fertile period of rehearsing, writing, recording, and touring, they added their hometown to their name: the Art Ensemble of Chicago was born. By 1970, drummer Don Moye – as fine a post-Max/Elvin era drummer as anyone not named Tony Williams or Jack DeJohnette – had completed the classic lineup.

From the outset, they agreed upon the same collaborative model that had made the AACM possible. Management of finances, creative decisions, sharing of money earned in outside opportunities (and these guys were in hot demand the entire time they were in Europe), all of these practices were a practical demonstration of the idealistic notions that the 60s are remembered for. One example: Bowie and his wife, Fontella Bass, had struck gold with “Rescue Me,” a few years earlier. They sold everything they had, including a Bentley automobile, to finance the move to Paris. And yet because these arrangements were born of necessity rather than whim, and were driven by a defined sense of purpose, the AEC managed to stay together and succeed in ways that relatively few communal projects do.

Roscoe Mitchell, Lester Bowie, Joseph Jarman, Malachi Favors Maghostut, Famoudou Don Moye: The Greatest Band in the History of Forever <fn>Wherein we recognize that calling anything/body the G.O.A.T. is simply shorthand for saying “my favorite.” I’ve had friends declaim the GOAT as (among many) The Who, Sex Pistols, Sleater Kinney, Phish, etc. Everybody is right; it’s just that I am righter.</fn> turned Europe on its ear with its presentation of Great Black Music: Ancient to the Future.

Great Black Music was the Art Ensemble’s strategy to escape the straitjacket marketing expectations and racist connotations of the label “jazz”. It was also a timely and direct assertion of their identity as Black Musicians at a time where the music industry was consolidating its ongoing practice of trying to whiten Black musics.<fn>See also, soft jazz and disco.</fn> The tag also allowed, as Mitchell once remarked, the group to freely access all music, not just the music that critics or marketers might insist they embrace. And that’s exactly what they did, with music that encompassed African, Caribbean cultures, the African-American classical tradition, the legacy of string bands and brass bands, gospel, field hollers, funk, rock, soul, and just about every other style under the Sun. Not for nothing did they call their music Sun Music and recite poetry extolling the virtues and exploits of the People of the Sun. Theirs was an expression of Black Power that never shied away from challenging their audiences, which in my experience were predominantly white. The AEC was not separatist. But they were most definitely radical.

(We once drove from Athens to Gainesville, FL, c. 1982, to see the AEC perform outdoors at some bandshell at the University of Florida. It was bizarre. A standard-issue platoon of SEC drunkwhitefratboys hand trucked a keg down to the field and did what standard-issue drunkwhitefratboys do when confronted with proudly Black and utterly expectation-defying entertainments. They heckled. They laughed and joked, they capered. They were not subtle. The band did not back down, raising their level of ferocity to match the bohunk brigade. I would swear at one point I heard one of the AEC chant, “N—–s here, get your n—–s here.” Fucking fearless.)

In Paris, the AEC set to work incorporating elements of theatrical ritual and dance, recitations, chant, kabuki and absurdist theater into their performances. On first glance these raucous happenings appeared to be uncontrolled and chaotic free-for-alls behind a wave of randomized sound. But repeated viewings and listenings revealed a carefully nurtured sense of structure and form, recognizable (if idiosyncratic) compositions, and tightly focused, exquisitely skilled instrumental tightrope trickery. Their “free” improvisation sections, largely unplanned beyond a basic instruction or framework, never devolved into pointless squalling. Untold hours of rehearsal taught them how to communicate in the moment and achieve consensus as to which direction to take, how to transition from one place to another – essentially, how to behave as conscious and cooperative human beings in a musical context. It was the musical expression of their larger organizational strategy of mutually supportive collaboration and decision making.

Every one of the group is a master at their craft. They all play(ed) multiple instruments, including their array of toys and noisemakers they dubbed little instruments. Eventually, their stage set would include dozens of reed and brass instruments. Several cages of gongs, bells, drums, shakers stood ready. Costuming ranged from Mitchell’s street clothes, to Bowie’s lab coat, to Jarman, Moye, and Favors various styles of face paint and uniforms, all carefully chosen to reflect connection to a range of traditions from America to Africa to the Far East. (Jarman became a Buddhist priest during his years with the AEC. Prior to the AACM, he had been in Vietnam. Details are skimpy, but he apparently spent some harsh time deep in the jungle behind enemy lines.)

The Art Ensemble of Chicago were/are anything but random. They worked with focus and commitment – to the music and to each other – in order to place themselves in a position to take advantage of opportunities that came their way. And at their peak, they were quite simply the best performing band on the planet.

The Big Ears Festival is celebrating two fiftieth anniversaries this year: both ECM Records and the Art Ensemble of Chicago debuted – separately – in 1969. Ten years later, the AEC would join ECM in what would be their most fertile commercial and (arguably) creative period. Certainly, their visibility would reach its peak during their ECM years. (They moved on to the Japanese DIW label c. 1986.) Talk about your harmonic convergence.

While AEC released only 4 albums under ECM during this time, they benefited from what amounted to major label support. ECM’s association with Warner Brothers gave them the best marketing and distribution support of their history. Late last year, ECM released a 21-CD box set that includes every ECM recording that featured any of the AEC members, along with a 296-page book chronicling their history with the label.

Even better, ECM viewed touring as a marketing activity for the recordings<fn>These days that equation is inverted.</fn> and provided full economic support for multiple tours of Europe, Japan, and North America. The AEC hauled several tons of equipment, so that support made possible their elaborate, full force presentations. It wasn’t just the music: the sheer theatricality of an AEC show – plus the fact that every night was dramatically different – was enough to make driving 10 hours to see a show like a bunch of Deadheads<fn>We did that for the Dead, too, fwiw.</fn> more than worth the effort.

This was the AEC that I encountered 40 years ago, the one that scrambled my DNA and set me on a path that brings me back around to the AEC/ECM birthday hullabaloo at Big Ears. Roscoe Mitchell mentioned last year that their 50th was coming, and I was pretty sure this was going to be part of the Big Ears menu this year. How could it not? And I remember thinking then that I would crawl over broken bottles to be there.

Of the original five, only Mitchell and Moye remain. I have no idea what to expect from the new lineup, which includes Hugh Ragin on trumpet, Junius Paul on bass, and Tomeka Reid on cello. I’m glad they are not trying to replicate the original lineup, though I imagine there is a certain philosophical orientation to the whole thing that evokes the AEC in their prime. Or maybe it will be something completely different, something I never expected to see in my wildest dreams, something that leaves me molecularily rearranged for my next 40 years. I’m willing to take the chance.

(I’ve written about my love of the Art Ensemble of Chicago before.

The Best. Band. Ever.<fn>ymmv</fn>)

Hat tip to Paul Steinbeck for his terrific AEC history Message to Our Folks. Another great resource is A Power Stronger Than Itself by George E Lewis, a massive history of the AACM. Get ’em.